Our Culture In Africa/Nuwaupia

African Empires to 1500 CE

The Kingdom of Aksum

In the sixth century, the kingdom of Aksum (Axum) was doing what many elsewhere had been doing: pursuing trade and empire. Despite the disintegration of the Roman Empire in the 400s and the decline in world trade, Aksum’s trade increased during that century. Its exports of ivory, glass crystal, brass and copper items, and perhaps slaves, among other things, had brought prosperity to the kingdom. Some people had become wealthy and cosmopolitan. Aksum’s port city on the Red Sea, Adulis, bustled with activity. Its agriculture and cattle breeding flourished. Aksum extended its rule to Nubia, across the Red Sea to Yemen, and it extended its rule to the northern Ethiopian Highlands and along the coast to Cape Guardafui.

From Aksum’s beginnings in the third century, Christianity there had spread. But at the peak of Christianity’s success, Aksum began its decline. In the late 600s, Aksum’s trade was diminished by the clash between Constantinople and the Sassanid Empire. The Sassanid Empire clashed with Constantinople over trade on the Red Sea and expanded into Yemen, driving Aksum out of Arabia. Then Islam united Arabia and began expanding. In the 700s, Muslim Arabs occupied the Dahlak Islands just off the coast of Adulis, which had been ruled by Aksum. The Arabs moved into the port city of Adulis, and Aksum’s trade by sea ended.

Aksum was now cut off from much of the world. Greek- the language of trade – declined there. Minted coins became rare. Paganism revived and mixed with Christianity. And it has been surmised that the productivity of soil in the area was being diminished by over-exploitation and the cutting down of trees. Taking advantage of Aksum’s weakness, the Bedja people, who had been living just north of Aksum, moved in. The people of Aksum, in turn, migrated into the Ethiopian Highlands, where they overran small farmers and settled at Amhara, among other nearby places. And with this migration a new Ethiopian civilization began.

West Africa

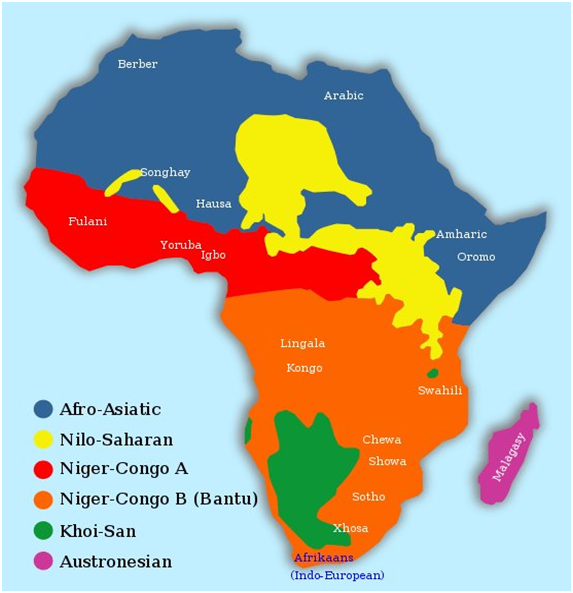

In West Africa, trade was giving rise to towns. There, on the fringes of the Sahara, arose a kingdom and empire that its rulers called Wagadu. The people of this kingdom were the Soninke — black people who spoke the language of Mande. Their king was called Ghana, and Ghana became the name by which this kingdom and empire became known — ancient Ghana rather than the modern state also called Ghana.

The kings of ancient Ghana were authoritarian. They inherited rule through their mother’s side of the family — matrilineal rather than patrilineal as with kings in Europe at the time — and they claimed descent from an original ancestor whom they believed had first settled the land. Ghana’s king was the leader of a religious cult that was served by devoted priests, and the king’s subjects were obliged to view him as divine and as too exalted to communicate directly with them.

Ghana’s kings had enhanced their power and enriched themselves by exploiting the trade passing through their territory. From the perspective of merchants they were not unlike highway bandits, forcing from tradesmen a tax on the gold they carried. But the tax was shrewder than robbery: a continual robbery would have ended the arrival of tradesmen carrying gold.

As Ghana’s kings grew richer they conquered, forcing obedience from the kings of other tribes, from whom they exacted tribute. They extended their rule to the gold producing regions to their south, and they imposed a tax on gold production.

Ghana’s major competitor was the Berber dominated city of Awdaghost to the northwest — a city with an ample supply of water, surrounded by herds of cattle and where millet, wheat, grapes, dates and figs were grown. The Berbers who dominated that city had wanted to make it the major point of passage for caravan trading across the western Sahara. But in 990 Ghana conquered the city, putting Ghana at the peak of its power.

Muslim Incursions

During Ghana’s days of glory, Muslim tradesmen were coming south in caravans from places like Sijilmasa, Tunis and Tripoli. From Sijilmasa the caravans had been going through Taghaza to Awdaghost. From Tunis and Tripoli they had been going to Hausaland and the Lake Chad region. They had been bringing salt southward, and they also carried cloth, copper, steel, cowry shells, glass beads, dates and figs. And they brought slaves for sale.

The Muslims were literate while the Soninke and their kings were not. The Soninke left no record of the doings of their kings. It was through Muslim writers that modern historians would gather what information they could about Ghana.

The Muslims were offended to find people worshiping their king as a divinity rather than worshiping Allah. The Muslims complained of people believing their kings to be the source of life, sickness, health and death. The Muslim writer al-Bakre described a Ghana king as having an army of 200,000 men, 40,000 of whom were archers. And he described the presence in Ghana of small horses.

Among the Soninke, the town of Kumbi had become a commercial center alongside a town of round mud-brick huts. Muslim tradesmen living there built stone houses and a number of mosques. Some Muslims there served as ministers at the king’s palace, and the town of Kumbi became an intellectual center for western Africa.

Muslim writers described one king of Ghana as renowned for his great wealth and the splendor of his court. The king held audience wearing fine fabrics and gold ornaments and bedecked his animals and retainers in gold. People in the north of Africa spoke of the king of Ghana as the richest monarch in the world.

But the power of the kings of Ghana was destined to end. Muslims in western Africa united behind the Almoravids — a Muslim dynasty that ruled in Morocco and Spain in the 11th and 12th centuries. A religious movement among the Muslims known as the Sanhaja inspired the Almoravids and others to a jihad (holy war), and Muslim Berbers in the Sahara joined an effort toward conversions and war against Ghana. The leader of the Sanhaja movement and army in the Sahara area, Abu Bakr, captured Awdaghost in 1054. And in 1076, after many battles, he captured the city of Kumbi.

Almoravid domination of Ghana lasted only a few years, but the Almoravids held onto control of the desert trade that had been dominated by Ghana. Without control of the gold trade, the power of Ghana’s kings declined further. They had, meanwhile, converted to Islam — while holding onto the religious rituals and myths that justified their rule to their subjects. Ghana’s kings allowed Berber herdsmen to move into Soninke homelands, and these herdsmen began overgrazing Ghana’s lands. Ghana’s agricultural land became worn and less able to support as many people as before. Subject kings and tribes broke away from Ghana’s rule. The king of the Sosso people, in neighboring Kaniaga, turned the tables on Ghana, and in 1203 the Sosso overran Ghana’s capital city, Kumbi.

The Mandingo Empire

After their victory over Ghana, the Sosso expanded against the Mandingo (or Mande) — a people who spoke Mande and lived on fertile farmland around Wangara. The Sosso king, Sumaguru Kante, put to death all of the sons of the Mandingo ruler but one, Sundjata, who appeared to be an insignificant cripple. But Sundjata rallied the Mandingo. A guerrilla army built by Sundjata overwhelmed the Sosso and in 1235 killed their king, Sumaguru Kante. Sundjata annexed Ghana in 1240, and he took control of the gold trade routes. Merchants moved out of Kumbi to another commercial city farther north: Walata. And in small groups the Soninke people began emigrating from what had been their homeland.

The empire that Sundjata created, called Mali, controlled the salt trade from Taghaza and the copper trade across the Sahara. The gold trade was a source of wealth for Mali, and so too was trade in food: sorghum, millet and rice. And regarding trade, Mali dominated the town of Timbuktu, nine miles north of the Niger River, which had risen a century or two before as a point of trade for desert caravans.

After Sundjata’s death in 1255 more conquests were made by his successors – Mansa Uli and then Sakura. Sakura had been a freed slave serving in the royal household and had seized power after the ruling family had become weakened by quarreling among themselves. It is surmised that Sakura was responsible for Mali’s expansion to Tekrur in the west and to Gao in the east.

By the 1300s, Mali’s kings had converted to Islam, which gave them advantages of good will in diplomacy and commerce. But, again, the pagan rituals and artifacts that were a part of the ideology and justification of rule were maintained. And the king’s loyal subjects continued their traditional prostrations and covering themselves with dust to display their humility.

By the 1300s, Muslim Mandingo merchants were trading as far east as the city-states in Hausaland and beyond to Lake Chad. Islam was spreading with the trade of its merchants, and it appears that in the 1300s or 1400s the kings of Hausaland converted to Islam. But when a Mali king tried to pressure people in the gold mining region around Wangara to convert, a disruption in the production of gold was threatened, and the pressure to convert was withdrawn.

One well known Mali emperor who was Muslim was Mansa Musa, who ruled from 1312-1337. On record is Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage to Mecca, his entourage described as including 500 slaves with gold staffs and 100 camels each with 300 pounds of gold. Mansa Mura is described as spending lavishly in the bazaars of Cairo and his spending is said to have increased the supply of gold to an extent that its price depreciated on the Cairo exchange. And, as usual, scholars were not immune from being influenced by wealth, Mansa Musa bringing a collection of them back with him from Mecca. Mali was literate, but only insofar as it employed Muslim scribes at the court of its kings. As in Europe, the common people of Mali were not yet expected to read and write.

The Songhai Rebellion and Mali’s Decline

Mali reached its peak in fame and fortune in the 1300s. Then weak and incompetent kings inherited power. Late in the 1300s the old problem of dynastic succession brought quarrels that weakened the Mali kingship and gave others opportunity.

The others in this instance were the Songhai people, who lived along the middle of the Niger River and monopolized fishing and canoe transport there. Trade at Gao had brought Islam to the Songhai. Some Songhai royalty had converted to Islam, as had an unknown percentage of Songhai commoners. Mali control over the Songhai capital, Gao, had always been tentative, and the spirit of independence had not died among Songhai kings. A Songhai king led his people in rebellion. The rebellion disrupted Mali’s trade on the Niger River. Mali’s empire suffered as the Songhai sacked and occupied Timbuktu in 1433-34. In 1464 a Songhai king, Sonni ‘Ali, took power, and again Timbuktu was attacked. Sonni ‘Ali captured the city after a great loss of life. Five years later, Sonni ‘Ali conquered the town of Jenne which had been thought impregnable. In his twenty-eight years of military campaigning, the victorious Songhai king won the title King of Kings. He dominated trade routes and the great grain producing region of the Niger River delta. Sonni ‘Ali’s competitor, the Mali empire, was deteriorating, and the Mali empire was to die in the 1600s.

Benin Exports Slaves

Benin was a city that dated back to the eleventh century — and no relation to the West African nation of Benin of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Benin was a large city for its time — a walled city several kilometers wide in a forested region inland from where the Niger River emptied into the Atlantic. In the mid-1400s the ruler of Benin, Ewuare, built up his military and began expanding. Captives taken in battle he traded to the Portuguese. Benin’s empire reached about 190 miles (300 kilometers) in width by the early 1500s. Then it stopped expanding, and with this it had no more captives to sell as slaves, while selling slaves to the Portuguese was being taken up by others.

160,000-year-old fossilized skulls uncovered in Ethiopia are oldest anatomically modern humans

Robert Sanders | 11 June 2003

BERKELEY – The fossilized skulls of two adults and one child discovered in the Afar region of eastern Ethiopia have been dated at 160,000 years, making them the oldest known fossils of modern humans, or Homo sapiens.

The skulls, dug up near a village called Herto, fill a major gap in the human fossil record, an era at the dawn of modern humans when the facial features and brain cases we recognize today as human first appeared.

The fossils date precisely from the time when biologists using genes to chart human evolution predicted that a genetic “Eve” lived somewhere in Africa and gave rise to all modern humans.

“We’ve lacked intermediate fossils between pre-humans and modern humans, between 100,000 and 300,000 years ago, and that’s where the Herto fossils fit,” said paleoanthropologist Tim White, professor of integrative biology at the University of California, Berkeley, and a co-leader of the team that excavated and analyzed the discovery site. “Now, the fossil record meshes with the molecular evidence.”

“With these new crania,” he added, “we can now see what our direct ancestors looked like.”

“This set of fossils is stupendous,” said team member F. Clark Howell, UC Berkeley professor emeritus of integrative biology and co-director with White of UC Berkeley’s Laboratory for Human Evolutionary Studies. “This is a truly revolutionary scientific discovery.”

Proof that Nuwpunu are Globally Indigenous

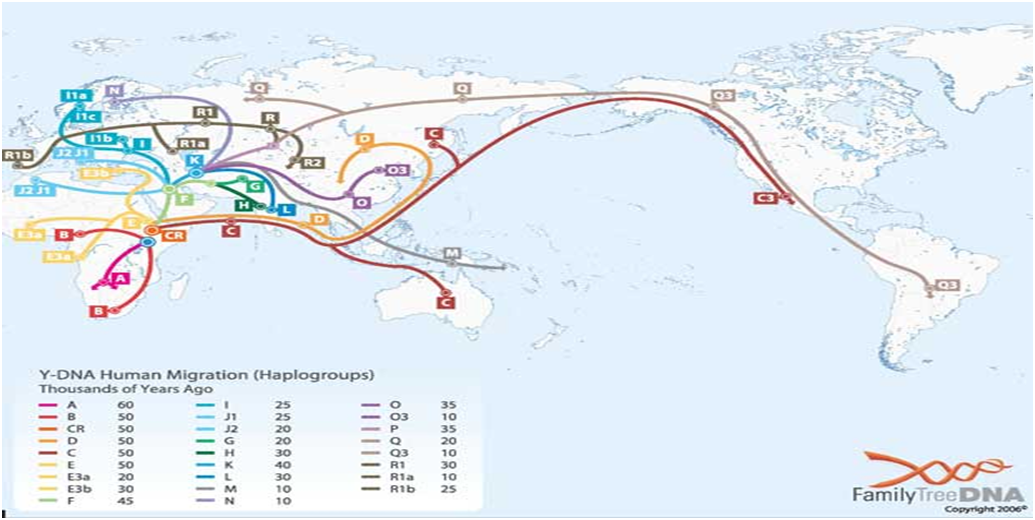

Prehistorians really agree that all of us originally came out of Africa. It’s the details that cause a paleoanthropological donnybrook.

by Joann C. Gutin

“For Old World prehistorians the heat has been fairly intense for the past five or six years. At issue has not been whether the earliest hominids evolved in Africa 3 million to 4 million years ago: fossils have made that, by now, beyond debate. Nor has there been any question that a subset of those hominids (in the shape of heavy-browed Homo erectus) left Africa about a million years ago; hand axes and fossils scattered throughout the Old World prove they were there.”

“That commonsense scenario–European H. erectus evolving into modern Europeans, Asian H. erectus into modern Asians–was badly shaken in 1987. That was when several biochemists from the University of California at Berkeley presented the phenomenon called mitochondrial Eve, in a six- page paper in Nature that abruptly turned the Old World evolutionary debate on its head. The research team, led by the late Allan Wilson, based its conclusions on genes, not bones, and asserted that there had been not one but two radiations out of Africa. The first was indeed by Homo erectus, but that one apparently didn’t take. It was the second radiation–at about 200,000 years ago–that counted; those emigrants were our ancestors.”

“Furthermore, the mtDNA that looked oldest–that, broadly speaking, had the most mutations–came from the women of African ancestry. According to the best estimates of mutation rate, that branch appeared to be about 200,000 years old. Q.E.D.: A small population of Africans had given rise to all modern humans. “

“The Clovis-friendly linguistic classification that answered the question was produced by Joseph Greenberg (an unorthodox scholar from Stanford whose ordering of the African linguistic picture had met with universal acclaim). His solution? All of these languages were related, he said. The first Paleo-Indians, suggested Greenberg, all spoke a common proto language when they drifted across the land bridge 12,000 years ago.”

“On the other hand, if all the native American languages come from one language brought to the continent in a single migration, the language clock says it must have happened 50,000 years ago.”

” Over the past 10,000 years, their data show, human evolution has occurred a hundred times more quickly than in any other period in our species’ history.”

“The new genetic adaptations, some 2,000 total, are not limited to the well-recognized differences among ethnic groups in superficial traits such as skin and eye color. The mutations relate to the brain, the digestive system, life span, immunity to pathogens, sperm production, and bones—in short, virtually every aspect of our functioning.

Many of these DNA variants are unique to their continent of origin, with provocative implications.” “It is likely that human races are evolving away from each other,” says University of Utah anthropologist Henry Harpending, who coauthored a major paper on recent human evolution. “We are getting less alike, not merging into a single mixed humanity.”

“The West Coast scientists were intrigued. On the basis of their own preliminary data, they, too, suspected that the pace of human evolution was accelerating. But they had arrived at the same crossroads by a different route. “We were focused on cultural shifts as a prime driving force of our evolution,” Moyzis says. As he explains it, an exceptional period in the history of our species occurred about 50,000 years ago. Humans were pouring forth from Africa and fanning out across the globe, eventually taking up residence in niches as diverse as the Arctic Circle, the rain forests of the Amazon, the foothills of the Himalayas, and the Australian outback. Improvements in clothing, shelter, and hunting techniques paved the way for this expansion.

Experts agree on that much but then part ways”

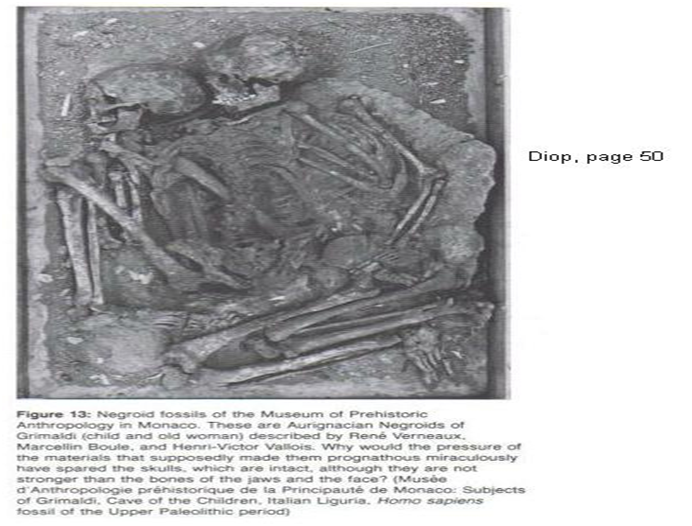

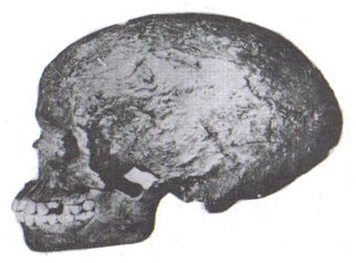

The Grimaldi or Negroid Type in Europe

Ancient Types of Man, (1911) Chapter VI, The Grimaldi or Negroid Type in Europe, page 59-63

In the cliffs which flank the beach near Men-tone there are a number of caves which for a long period of time afforded a habitation for ancient man. At the close of the last and at the beginning of the present century, largely owing to the interest taken in the history of primitive man by the Prince of Monaco, systematic excavations were carried out in deep strata of their floors. In one of these, the “Grotte des Enfants,” usually named the Grimaldi Cave, the various strata of the floor made up a thickness of 8 1/2 metres (28 feet). In the lowest layer of all were found two years of age, and about 1550 mm. (5 ft. 1 in.) in height.

With them were found traces of a civilization and of a fauna which has led anthropologists to assign them to the end of the Mousterien or beginning of the Aurignacien Period [40,000 to 28,000 years ago]—about the same or perhaps before the period assigned to the Combe-Capelle man. They have the narrow and long heads of the Galley Hill race. In the woman the maximum length of the head is 191 mm.; in the boy, probably her son, it is 192 ; the width of the skull in the mother is 131 and in the son 133. The proportion of breadth to length is about 68 per cent—the same as in the Galley Hill race. Yet French anthopologist Dr. Verneau,(1) who has published the results of a minute examination of these two ancient individuals, from various features seen in the skeletons, had no hesitation in assigning them to a negroid race.

The Grimaldi Negroids have left their numerous traces all over Europe and Asia, from the Iberian Peninsula to Lake Baykal in Siberia, passing through France, Austria, the Crimea, and the Basin of Don, etc. In these last two regions, the late Soviet Professor Mikhail Gerasimov, a scholar of rare objectivity, identified the Negroid type from skulls found in the Middle Mousterian period.

If one bases one’s judgment on morphology, the first White appeared only around 20,000 years ago: the Cro-Magnon Man. He is probably the result of a mutation from the Grimaldi Negroid due to an existence of 20,000 years in the excessively cold climate of Europe at the end of the last glaciation.

The Basques, who live today in the Franco-Catabrian region where the Cro-Magnon was born, would be his descendants; in any case there are many of them in the southern region of France.

Ancient Civilization Of South Africa

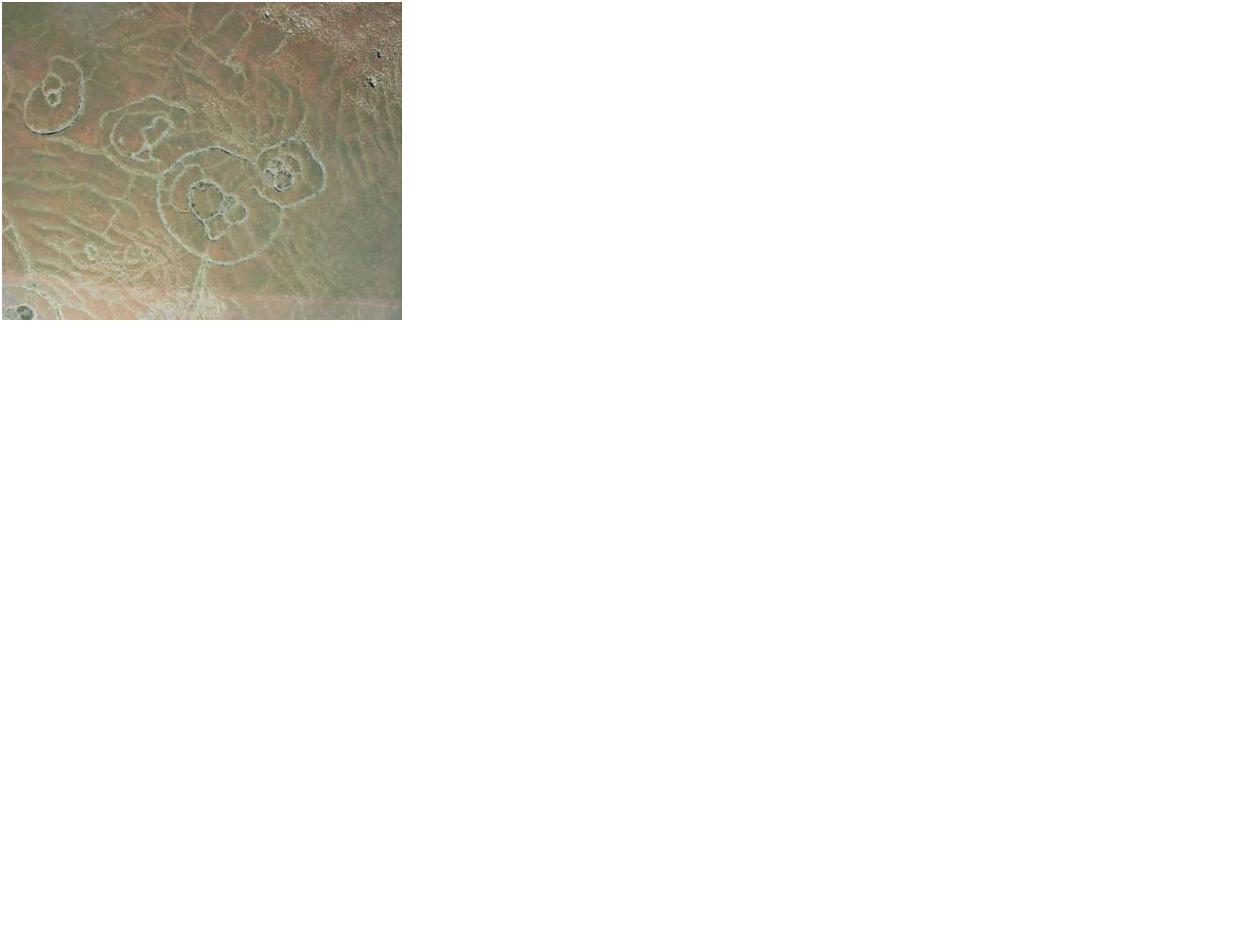

When historians first stumbled upon these structures they simply assumed that they were cattle kraal left behind by the Bantu people as they moved south and settled the land from around the 13th century.

But research work done by people like Cyril Hromnik, Richard Wade, Johan Heine and a handful of others over the past twenty years, into ancient southern African history, has revealed that these stone structures are in fact more than just cattle kraal, but the remains of ancient temples and astronomical observatories of lost ancient civilizations that stretch back for thousands of years.

These circular ruins are spread over thousands of square kilometers. They can only truly be appreciated from the air, and those lucky enough to view these ruins from the air will be able to see hundreds of ruins in a one-hour trip.

The discovery of the ancient stone calendar site by Johan Heine (Adam’s Calendar) in among all these stone dwellings and temples, would suggest that some of the structures would date back to the same era as the calendar some 75,000 years ago.

It shows us with a certain level of clarity that these lost civilizations have been around for much longer than anyone could ever have imagined.

It would not be absurd to then suggest that we may be staring at the very first concentrated human settlements inhabited by the early Homo sapiens.

[Become A Member – sign up today]